Parents want their children to have a successful education, and that is no less true of parents of children with Down syndrome. However, many schools don’t have a lot of experience educating children with Down syndrome and may not be familiar with best practices. As a parent, you can empower yourself and your child’s educational team with information about the Down syndrome learning profile and about the supports available to help your child succeed in school.

We talked to Nancy Litteken, executive director of Club 21 Learning and Resource Center in Pasadena, and Emily Mondschein, executive director of Gigi’s Playhouse in Buffalo, New York, both of whom are also parents of individuals with Down syndrome. We also spoke with neuropsychologist Dr. Ann Simun, of Simun Psychological Assessment Group, and Dr. Sarah Pelangka, special education advocate and owner of KnowIEPs, to gain expert insight into what families need.

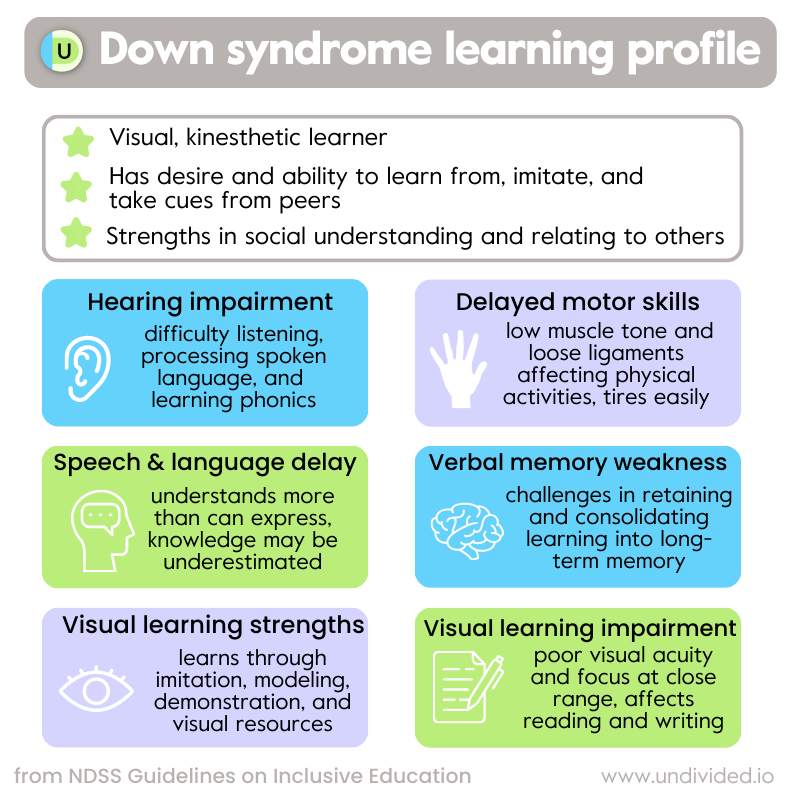

Sue Buckley, a psychologist and a leading expert in education and development for young people with Down syndrome in the UK, has devoted her career to researching the way children with Down syndrome learn. Buckley has created a widely referenced Down syndrome learning profile. Nancy Litteken and Emily Mondschein emphasize that this learning profile provides helpful information for parents as well as for teachers, therapists, and pediatricians. Mondschein and the National Down Syndrome Society (NDSS) have integrated Buckley’s Down syndrome learning profile into NDSS’s Guidelines on Inclusive Education.

Mondschein explains how parents can use the guidelines to inform their children’s teachers, therapists, and medical professionals.

One key takeaway from the Down syndrome learning profile is behavior. Professor Buckley tells us that any individual will draw on their strengths to solve problems and overcome challenges. Since social skills are a relative strength for individuals with Down syndrome, they will often attempt to solve other problems using these skills. For example, when faced with a math problem in class, skills in abstract thinking should be used to solve the problem. Since this is an area of weakness for many individuals with Down syndrome, they might instead try to engage their peers or teacher to help, using humor or silly faces to try to make the other person feel enough kindness to solve the problem.

It's a survival tactic that backfires within the rigid structure of our education system. Instead, teachers can draw on the student’s social aptitude to pivot into developing other skills. Many children with Down syndrome have an aptitude for imitation, which can be effectively used in an inclusive learning environment. For example, a child with Down syndrome can be paired with typically developing peers in group work on a science project. Working with others will feel motivating, and finding ways to contribute can develop their communication skills. They might find a role in the group as the presenter or by taking photos of the group work.

Mondschein reminds us that the profile is only a guide — each individual with Down syndrome is unique: “Individuals with Down syndrome tend to have a very strong social strength, but my son does not, and so I always remember when I talk about this profile that if you know one person with Down syndrome, you only know one person with Down syndrome. It's all unique individuals, but there just are certain commonalities, and the social piece does happen to be one of the strengths we found when we studied the population as a whole.”

The profile shows that children with Down syndrome usually have strengths in social skills relative to their developmental age. While the learning challenges for kids with DS are often related to working memory, auditory and short-term memory present the most challenges. However, stimulating the visual memory can help students access long-term learning.

Litteken tells us that for individuals with Down syndrome, long-term memory, not short-term memory, is their strength, and that repetition is key: “Listening is not their strength. Visual is their strength. They have a strong visual awareness and visual learning skills. If they can see it or picture it to storyboard it, watch it on a video, see it on an iPad again and again — all of those things are their strengths. So using signs and gestures, any visual supports, or pictures is huge. And that's an important piece. They have the ability and can use the ability to read the written word with all those things come into practice. But they need the structure and they need the routine and they need the repetition.” Visual supports are a key accommodation in school as many teachers, especially in middle and high school, deliver much of their teaching through verbal lecture.

Research has shown that while most individuals with DS have very weak working memory — especially auditory memory — they can increase their memory capacity with training. Playing memory games and exercises can stretch their skills, which pivots into other useful learning; this can also be improved through specific educational therapy with an experienced provider. . Successful teaching strategies include using visual stimuli to prompt the longer term visual memory.

Some people doubt that children with Down syndrome can learn to read, but that is untrue. Many children with DS are exceptionally good readers, learning as young as age three or four. An added benefit of reading is that it can assist in the development of speech and language. Reading is a key skill which is often associated with greater independence as an adult.

While reading is often a strength for children with DS, they are likely to need 1:1 intensive reading instruction. Reading experts Sue Buckley, Patricia Oelwein, and Terry Brown agree that an effective reading strategy for children with DS uses high-interest sight words and personal books, which capitalizes on social and visual strengths. A strategy based on sight words, also known as whole-word approach, is effective because phonemic awareness, especially rhyming, is a challenge and may be delayed. For many experts in teaching reading to children with DS, a whole-word approach is a good starting point, but recent research suggests that explicit instruction in phonics (structured literacy) is also effective for children with DS. For more information about the science of reading applied to students with Down syndrome see this resource from the Down Syndrome Resource Foundation.

Many families find reading programs outside of school since so few public schools have expertise in teaching children with Down syndrome to read. A few such programs include See and Learn by Down Syndrome Education International (established by Sue Buckley), Every Child A Reader literacy tutoring through Club 21, Special Reads by Natalie Hale, So Happy to Learn by Terry Brown, and 1:1 Literacy Tutoring Program through Gigi’s Playhouse. You can listen to Emily Mondschein talk about how they teach reading at Gigi’s Playhouse here.

Reading comprehension in particular can pose challenges for students with Down syndrome, although it isn't always clear whether the challenge is in comprehending or in demonstrating comprehension, since many children with DS struggle with answering comprehension questions. Offering alternative ways to demonstrate understanding can be beneficial. For example, as Mondschein explains, “Can they point to something? Can they sign it? Can they gesture? Can they draw it? Do you have an assistive device to show that they know comprehension? You really have to stretch to make sure you're providing ways for them to show that they have comprehension strategies, because you might not think they do, and then they in fact do.” For many children with auditory memory deficits, multiple choice, matching or other recognition tasks are more effective to show their knowledge than are open ended questions.

Mondschein specifically suggests having a 10- to 20-minute daily separate block of reading that's focused on an individualized reading approach, separate from reading alongside their typically developing peers.

Low muscle tone, short-term memory issues, and intellectual disability make learning to write a challenge. Trying to learn handwriting before a child’s fingers are strong enough is likely to lead to frustration and poor pencil grasp. Occupational therapy can help children with Down syndrome learn to write. However, it may always be a challenge. Assistive technology can also help reduce barriers to learning by supporting spelling, expressive writing, and typing skills. You, together with your child’s IEP team, can request an AT assessment if you decide one is necessary. Find examples of AT in our article here.

Math: Children with DS can learn math! They often need visuals and manipulatives, such as those found in curricula like TouchMath and Numicon. Parents can also do at-home math learning activities. In addition, challenges in short-term memory may require children with DS to continually practice skills already mastered. Keep in mind, too, that children with DS don’t always demonstrate their skills with 100% mastery. A child who can’t accurately count to 20 each time may still be able to master fourth- or fifth-grade math skills. And while TouchMath is a great resource, Dr. Pelangka explains that parents can also consider more functional approaches to support the mastery of math concepts, such as using tools like calculators.

Science and social studies: Like everyone, adults with DS will need to understand something about their world and society. Sometimes, education teams gloss over science and social studies, thinking it most important to educate a child in the core skills of language arts and mathematics. However, subjects such as science and social studies are important so that people with DS can effectively understand and participate in the world around them. “Science also has a lot of project-based learning, which means more social interaction, a great space for students with DS to capitalize on their social strength,” Dr. Pelangka tells us.

Health education: Some children with intellectual disabilities are not given access to health and sex education curricula. There is a myth that people with Down syndrome are “perpetual children,” and this is simply not true. Teens and adults with DS experience the same desires as typically developing people, and it’s important that they be exposed to the same education on the topic, including how to keep themselves safe.

Second language learning: Particularly in California, which is home to many families who speak multiple languages, you might wonder whether your child with Down syndrome can learn another language. In fact, research shows that children with Down syndrome can learn a second language. Children with DS can also learn ASL as a form of communication.

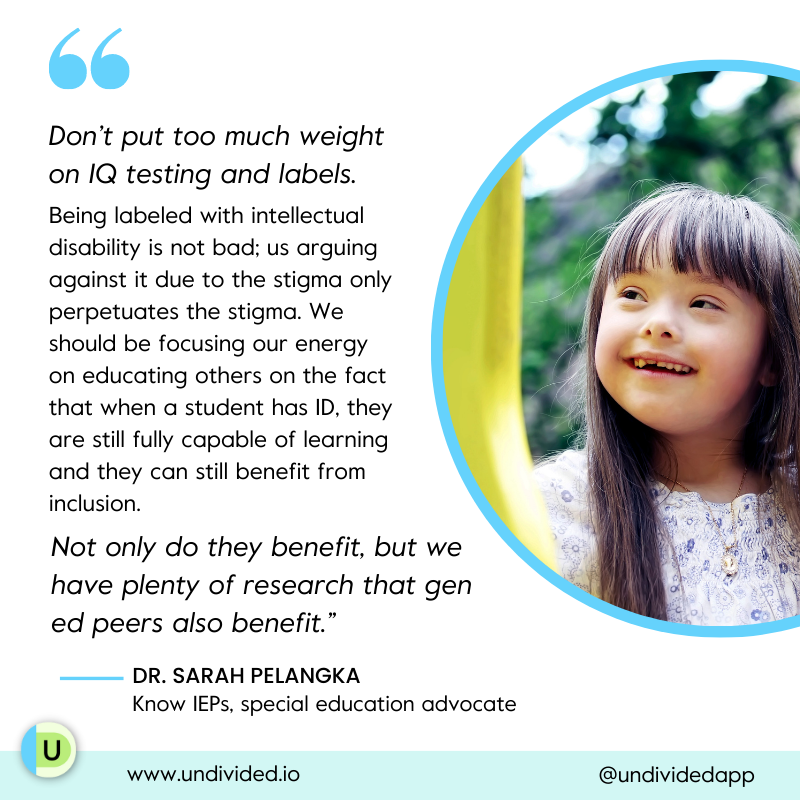

Many educators are not aware of the DS learning profile. IEP teams often rely instead on outdated information, myths, and standardized tests, such as IQ tests, to create an individual learning profile for each child. The negative stigma for Intellectual Disability (ID) continues in the education community as does the assumption that all children with DS have ID. Both Litteken and Mondschein, whom are also parents of individuals with Down syndrome, feel that IQ tests are not helpful.

Mondschein says, “I avoid the tests. I feel like our children do not do well on them. You know, whether it's a writing piece or a verbal piece, I always worried as a caregiver, as a parent, that people would judge my son based on a number that didn't particularly show his strengths. It would only horribly highlight his weaknesses. That was always my feeling. I don't think IQ scores should be relevant to a child's placement. And I also feel that we have enough information from our related services notes, our classroom teacher notes, and special education — all the different little assessments they're doing day in and day out. I think those are the most important assessments we're looking at. I don't think that a lot of important information and data is going to be learned from an IQ test. I don't think it's going to give a true read on our individuals. Half the time, they will break standardization. They'll give an answer and they'll show their ability, but they already broke standardization and it can't be recorded. So I don't see the point.”

Neuropsychologist Dr. Ann Simun, on the other hand, tells parents not to be afraid of a number; the test should have various parts and each part has a score which can tell you a lot of information about how your individual child learns. “I think it's more important as to HOW we are measuring cognitive ability than avoiding measuring it altogether,” she tells us. If the person who conducted the test cannot use the information to explain how the child learns the best, you may need a more experienced evaluator. A child should never be described solely by a unitary score; the tests are not designed to be used in that manner. As noted above, having an accurate measure from a person experienced with DS is important.

Dr. Simun adds that there are a wide range of IQ tests. Parents can educate providers about a child’s known challenges, specifically attention span, processing speed, motor skills, auditory processing delays, which can negatively impact a valid measure of cognitive ability. Many school psychologists give the same tests to all children regardless of their challenges; however, those with significant motor impairments and poor pencil skills should not have their IQ measured by the use of paper-pencil tasks, such as as found on the CAS or the WISC/WAIS. Attention span and processing speed negatively impact timed tests. Tests such as the CTONI, Leiter, and others are untimed, and may more validly measure abilities. The KABC has an untimed version, which can be more valid for those with short attention span or slower processing speed. The key is to ensure that your evaluator is knowledgeable about DS and will select the measures appropriately, and to interpret those findings accurately.

Dr. Pelangka adds that besides IQ tests, parents should know that there are many different cognitive tests at their disposal, some more appropriate for individuals with DS than others, as well as processing measures, which can tease out how the child learns best and how to best present material to the student. “No one test should dictate any educational decisions; the entirety of the data should be taken into consideration,” she says. Read more about IQ testing, and your options as a parent, in our article Intellectual Disability 101.

Because Down syndrome is not an eligibility category for special education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), children with Down syndrome are most often found eligible under the category Intellectual Disability. For this eligibility to be determined, the school needs to assess that the child’s cognitive ability is below average. It is common, but not strictly necessary, to use a standardized IQ test. Mondschien joins NDSS in suggesting that an eligibility category for Down syndrome might address this issue. Many students with SD are qualified instead under Other Health Impairment; many may also qualify under Speech Language Impairment.

You can request that your IEP team consider eligibility under Speech and Language Disorder or Other Health Impairment. Many families prefer these categories because of the stigma attached to intellectual disability, the difficulty of performing a valid standardized test given a child’s communication, attention and motor issues, and the fact that so many children with intellectual disabilities are educated in more restrictive settings despite the decades of research showing that this is less effective for long-term outcomes than supported inclusion.

Just because a 3-year-old qualifies for placement in a specific special education classroom doesn’t mean they must attend that classroom. The best setting for your child at school will depend on many things, including goals, instruction, related services, and any supports they need to make meaningful progress academically and socially. IDEA protects a child’s right to inclusive education, and studies have shown that special education as a service offered in a classroom with typically developing peers is most effective.

Litteken explains why inclusive education is a priority for children with Down syndrome, telling us that inclusion “is the gateway to building peer relationships” and will help with social communication and improve academic and peer relationships. All of those connect us with what we all want in life, which is to have friends, belong to a group of people, and know that we can contribute to society.

“If you've never done it before, it's really hard. And I think that's why that long-term vision is really important. I am not saying anything about this is easy. I'm not saying anything about this does not come with exceptions, or seasons of exceptions, [but] I think it's really important for you to think, and have a school district think, ‘When do I get out of special ed? Is there a plan to get out?’”

She suggests going back to what the research says and your long-term vision for your child.

Dr. Pelangka adds, “Individuals with DS are excellent imitators, and we want them to learn and imitate their gen ed peers, not the limited language and increased maladaptive behavior models they may see in the restricted settings.”

Research of several decades has shown that the long-term outcomes for students with disabilities are generally better for those with appropriately supported inclusion than for those who are fully segregated. Each child’s needs should be considered when examining placement, but many school districts automatically recommend segregated settings such as “Special Day Class” (whether mild/moderate or moderate/severe) for children with ID eligibility. This trend is not supported by the research, however. Even students who are in a segregated placement should have supported time integrating or mainstreaming with their same-aged peers.

Mondschein explains why inclusive education is important, especially given the history of exclusion of people with Down syndrome from society:

In addition to improved educational outcomes, inclusion helps fulfill an individual’s need to belong. Litteken explains that every human has a desire to belong, and belonging is tied to life satisfaction and mental and physical health. It gives you a sense of where you are in the world and gives you purpose and meaning. Ultimately, it is up to you, together with your child’s IEP team, to determine what is the best fit for your child.

To succeed in school, you’ll want your child to have a solid individualized education program (IEP) based on their strengths. Your school may not have expertise in educating children with Down syndrome based on their strengths in visual learning and social skills, so you’ll need to bring your child’s strengths to the team’s attention. Litteken emphasizes the need for parents to advocate and bring their child’s individual strengths to the IEP table.

Mondschein says that parents often have to advocate for inclusion when their children are not performing at grade level. “Educators need to remember that…we have these goals, and these goals, by the way, don't have to be on grade level, right? Maybe they're reading at what the school determines a first-grade level, they're in fourth grade — that does not mean they need to be removed from the classroom. As long as we have quite accessible goals in place for the student and the student is progressing towards their own goals, then they should not be removed from that classroom. And we are also making sure, before we even contemplate that, that we have exhausted all the accommodations and the supplementary aids and the modifications. We have done all of that before we decide to remove a student from a gen ed setting.”

Mondschein summarizes what needs to be in an IEP for a child with DS:

Hopefully, your child’s team will be responsive, and you’ll be able to collaborate to create a strong IEP. However, sometimes schools are not as open to input as one might like; in such a case, you may need to access professional support for your IEP, such as a special education advocate or an attorney.

Sometimes, school team members may need to be reminded that a child on an IEP may be on a modified curriculum, for some or all subjects, even if those goals are being addressed in the general education setting for all or part of the day. As eligibility/diagnosis does not determine setting, curriculum also does not dictate setting.

We’ve compiled the following list of accommodations that students with DS may need. Please note that this list is not exhaustive but is a starting point to use when discussing accommodations and supports with your IEP team. It’s important to “Presume Competence” — every child with DS is different and we don’t want to limit them by encouraging accommodations that aren't needed. This is a list of common accommodations but not every child with DS needs every accommodation listed. Accommodations should be addressed within their own highly individual and specific IEP.

Schools should provide occupational therapy (OT), physical therapy (PT), and speech therapy as needed. Some children with Down syndrome have accomplished their PT goals by the time they enter elementary school, but most still require OT and speech services, as these skills may take longer to develop and refine. Sometimes, schools will only give group speech (and often only 30 minutes a week), so parents may want to advocate for strong 1:1 speech support. Dr. Pelangka tells us that it will always depend on the student’s needs: “Whenever a student is learning how to navigate an AAC device, I always recommend 1:1 as they need that direct support in learning their device. Also, when a student is working on articulation, they need intense 1:1 sessions (generally at least 15 minutes per week). However, without peers, there is no work on social communication, and many students benefit from those peer models, so group therapy can be great. Ensure that parents ask how many peers will be in the group and if they are all working on similar skill sets, and ask to see the data from the sessions.”

She continues, “Many Functional Skills or Mod/Severe programs (think county programs) offer ‘whole group’ push-in services, whereby they say the classroom or program itself ‘offers the supports embedded within it.’ The SLP comes in weekly and works with the class as a whole. Be wary of this; I always say, ‘How can it be possible that every student is working on the same goals, and even if that were a possibility, that they would each get enough time to receive benefit from this?’ This is a tactic that is used due to the SLPs not having enough time — not your child’s problem. Fight for 1:1 or small group services. They will write it as ‘Group’ — ask for ‘Small Group.’”

Mondschein explains the effectiveness of doing “push-in” support for things like OT, PT, and speech, rather than pulling a child out of class to work on these skills: “When you're doing OT, maybe it's more meaningful to be cutting and pasting during the actual time that it's happening, during real time in the classroom. So it's a great way for the OT to come into the room and support that. Same with PT — can we make that in the gym? Can we make that in physical education class? Can we go out on the playground? Speech — have those real interactions with peers, and the speech pathologist can sort of facilitate that. So there's some really neat ways that we can bring related services into the classroom and have them be more effective.” Push-in services are something you can advocate for during your child’s IEP meeting.

Dr. Simun adds that speech and language goals should be written with an eye toward the future, and we want to see these skills demonstrated in all settings, especially group classroom, inclusion or mainstreaming, and social settings such as recess. It is often a good idea to have all people on the instructional team listed as responsible for the communication goals.

Speech and writing can be overwhelming challenges for children with DS since they can be impacted by motor impairments such as hypotonia and by developmental and cognitive delay. For this reason, an important accommodation is to use a total communication strategy that allows children alternative ways to express themselves in speech and writing. Parents should request both an AAC evaluation and an assistive technology evaluation for oral and written expression on a regular basis throughout their educational career. If AAC is implemented, all members of the educational team and the family should be provided with training and support in how to use the device and how to support the student. When AAC is only used in one setting, such as the speech therapy room, it is unlikely to generalize to other settings, and this can hamper long-term independence.

Some children with Down syndrome will need behavior support, which can be provided through a Functional Behavior Assessment and the development of a behavioral intervention plan (BIP) or Behavior Support Plan (BSP). A child who is placed in a general education classroom may need a paraeducator or behavior interventionist for support, but be careful that this does not reduce independence. Children with Down syndrome sometimes engage in learned helplessness, where if they know someone will help them with a challenging task, they will rely on that person instead of stepping up to the task themself. A good paraeducator will work quietly in the background to support your child when needed, stepping back to allow independence whenever possible. Paraeducators are an accommodation to help children with Down syndrome access the curriculum in the general education classroom. They are a support, and they don’t actually change what the child is learning. Modifications, on the other hand, change the expectations of what a child will learn in the general education classroom.

Virtually all children with Down syndrome will have accommodations in general education classes; some will also need a modified curriculum as the gap between their knowledge and that of their typically developing peers widens. Note that a large degree of modification may prevent your child from graduating with a diploma. Some individuals with Down syndrome are able to graduate from high school with a diploma. Others will finish school with a certificate of completion or through an alternate pathway to a diploma. Early placement in a functional skills program can have a great impact on a child's ability to complete the requirements for a high school diploma.

A benefit of the certificate program is that an IEP can allow for additional years of education, up through age 22 in some states. This support is typically not provided if a diploma is earned, as the attainment of the diploma ends the IEP process for the student. Another alternative is delayed graduation; students who need more time to complete their required courses again may continue to take coursework through age 21 or 22 depending on your state. Many young adults with Down syndrome are able to enjoy a college experience even if they do not graduate with a high school diploma. There are now many college programs designed for individuals with intellectual disabilities.

There are many ways to support our kids’ learning and development, whether that’s doing activities, playing, and learning at home with them, or helping them feel safe and included in the community. Dr. Pelangka gives us a few tips for parents when navigating learning and school systems:

School supports and parental rights: “We should be educating families on their rights to question cognitive testing — what instruments were used and whether the results are in fact valid measurements based on their child’s disability. We should be educating parents on understanding their rights as far as receiving a full, comprehensive overview of the report such that they fully understand their child strengths and weaknesses, and then we need to assist parents in using that information to ensure their child’s IEP is comprehensive and written to their child’s strengths and to support their areas of need. The expectation should never be to close the gap. The law doesn’t say that either. The expectation should be to challenge the student, write a meaningfully challenging IEP, and ensure that the student is in the least restrictive environment possible to meet said goals,” Dr. Pelangka continues.

Dr. Simun adds that a specific right that parents may be less aware of is the right to disagree with the findings of the school evaluations, and request an outside evaluation at district expense; this is called an Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE). However, when selecting an IEE provider, it is important parents ask the right questions to ensure that the new assessment does not repeat the mistakes of the disputed assessment.

Informed and involved: “Lastly,” Dr. Pelangka says, “we need to ensure that parents understand how to analyze the data. Just because a team reports that a student is/is not progressing doesn’t mean that’s accurate. Ask for the data and ensure that you know what you are looking at. Also, conduct frequent observations of your child in their learning environment (or send a blind observer in so the student’s behavior doesn’t change when they see their parent) and get neutral information on what is truly happening. Odds are it’s the environment that needs changing, not the child.”

Belonging: Litteken also tells us that it’s our job to make sure they know that they belong, whether that’s at home, at school, college, or beyond: “I think there's a mindset that they are important in this world and belong and that they can do amazing and hard things. And the mindset is: my job is to cheer them on. My job is to figure out what they're good at and what they love… Expect the unexpected. I think you'll be surprised, and if you prepare yourself for joy and surprises and personality and this little human’s own spark — regardless of the diagnosis or medical issues — if you can say, 'What's in there?’ you will find possibilities.”